A few weeks ago I wrote

How decentralized is Bluesky really?,

a blogpost which received far more attention than I expected on the

fediverse and Bluesky both. Thankfully, the blogpost was received

well generally, including by Bluesky's team. Bryan Newbold, core

Bluesky engineer, wrote a thoughtful response article:

Reply on Bluesky and Decentralization,

which I consider worth reading.

I have meant to reply for a bit, but life has been busy. We launched

a fundraising campaign over at Spritely

and while I consider it important to shake out the topics in this blog

series, that work has taken priority. So it is about a week and a

half later than I would like, but here are my final thoughts (for my

blog at least) on Bluesky and decentralization.

For the most part, if you've read my previous piece, you'll remember

that my assertion was that Bluesky was neither decentralized nor

federated. In my opinion many of the points raised in Bryan's article

solidify those arguments and concerns. But I still think "credible

exit" remains a "valuable value" for Bluesky. Furthermore, Bryan

specifically solicited a request to highlight the values of

ActivityPub and Spritely, so I will do so here. Finally, we'll

conclude by what I think is the most important thing: what's a

positive path forward from here?

Some high-level meta about this exchange

Before we get back into protocol-analysis territory, and for that

matter, protocol-analysis-analysis, I suppose I'd like to do some

protocol-analysis-analysis-analysis, which is to say, talk about the

posting of and response to my original blogpost. Skip ahead if you

don't care about this kind of thing, but I think there are interesting

things to say about the discourse and meta-discourse of technology

analysis both generally and how it has played out here.

Much talk of technology tends to treat said tech to be as socially

neutral as a hammer. When I buy a hammer from a hardware store, it

feels pretty neutral and bland to me. But of course the invention of

the hammer had massive social ramifications, the refinement of its

design was performed by many humans, and the manufacture of said

hammer happens within social contexts of which I am largely

disconnected. To someone, the manufacture and design of hammers is I

am sure deeply personal, even though it is not to me.

To me, decentralized networking tech standards and protocols and

software are deeply personal territory. I have poured many years of

my life into them, I have had challenging meetings where I fought for

things I believed important. I have made many concessions in

standards which I really did not want, but where something else was

more important, and we had to come to agreement, so a compromise was

made. I write code and I work on projects that I believe in. To me,

tech is deeply personal, especially decentralized networking tech.

So it took me a long time and effort and thinking to write the

previous piece, not only because I wanted to put down my technical

analysis carefully, but because I have empathy for how hearing a

critique of tech you have poured your life into feels.

I probably would not have written anything if it were actually not for

the invitation and encouragement of Bryan Newbold, whose piece is the

"Re:" in this "Re: Re:" article. People had been asking me what I

thought about ATProto and I said on a public fediverse thread that I

had been "holding my tongue". Bryan reached out and said he would be

"honored" if I wrote up my thoughts. So I did.

So I tried to be empathetic, but I still didn't want to hold back on

technical critique. If I was going to give a technical critique, I

would give the whole thing. The previous post was... a lot. Roughly

24 pages of technical critique. That's a lot to be thrown at you,

invitation or otherwise. So when I went to finally post the article,

I sighed and said to Morgan, "time for people to be mad at me on the

internet."

I then posted the article, and absurdly, summarized all 24 pages of

tech in social media threads both

on the fediverse

and on bluesky.

I say "summarized" but I think I restated nearly every point and also

a few more. It took me approximately eight hours, a full work day,

to summarize the thing.

And people... by and large weren't mad! (For the most part. Well,

some Nostr fans were mad, but I was pretty hard on Nostr's

uncomfortable vibes, which I still stand by my feelings on that.

Everyone else who was initially upset said they were happy with things

once they actually read it.) This includes Bluesky's engineering

team, which responded fairly positively and thoughtfully overall, and

a few even said it was the first critique of ATProto they thought was

worthwhile.

After finishing posting the thread, I reached out to a friend who is a

huge Bluesky fan and was happy to hear she was happy with it too and

that it had gotten her motivated to work on decentralized network

protocol stuff herself again. I asked if the piece seemed mean to

her, because she was one of the people I kept in mind as "someone I

wouldn't want to be upset with me when reading the article", and she

said something like "I think the only way in which you could be

considered mean was that you were unrelentingly accurate in your

technical analysis." But she was overall happy, so I considered that

a success.

Why am I bringing this up at all? I guess to me it feels like the

general assessment is that "civility is dead" when it comes to any

sort of argument these days. You can't win by being polite, and the

trolls will always try to use it against you, don't bother. And

the majority of tech critiques that one sees online are scathingly,

drippingly, caustically venomous, because that's what gets one the

most attention. So I guess it's worth seeing that here's an example

where that's definitively not the case. I'm glad Bryan's reply was

thoughtful and nice as well.

Finally, speaking of things that one is told that simply don't work

anymore, my previous article was so long I was sure nobody would

read it. And, truth be told, people maybe mostly read the social

media threads that summarized it in bitesized chunks, but there were

so many of those bitesized chunks. As a little game, I hid "easter

eggs" throughout the social media threads and encouraged people to

announce when they found them. For whatever reason, the majority of

people who reported finding them were on the fediverse. So from a

collective standpoint, congratulations to the fediverse for your

thorough reading, for collective collection of the egg triforce, and

for defeating Gender Ganon.

Okay, that's enough meta and meta-meta and so on. Let's hop over to

the tech analysis.

Interesting notes and helpful acknowledgments

Doing everything out of order of what one would be considered

"recommendable writing style", I am putting some of the least

important tidbits up front, but I think these are interesting and in

some ways open the framing for the most important parts that come

next. I wanted to highlight some direct quotes from Bryan's article

and just comment on them here, just some miscellaneous things that I

thought were interesting. If you want to see more pointed, specific

responses, jump ahead again to the next section.

Anything you see quoted in this section comes straight from

Bryan's article,

so take that as implicit.

A technical debate, but a polite one

First off:

I am so happy and grateful that Christine took the time to write

up her thoughts and put them out in public. Her writing sheds light

on substantive differences between protocols and projects, and

raises the bar on analysis in this space.

I've already said above that I am glad the exchange has been a

positive one and I'm grateful to see that my writing was well

received. So just highlighting this as an opening to that.

However, I disagree with some of the analysis, and have a couple

specific points to correct.

I highlight this only to remind that despite the polite exchange, and

several acknowledgments about things Bryan does say I am right about,

there are some real points of disagreement which are highlighted in

Bryan's article, and that's mostly what I'll be responding to.

"Shared heap" and "message passing" seem to stick

Christine makes the distinction between "message passing" systems

(email, XMPP, and ActivityPub) and "shared heap" systems

(atproto). Yes! They are very different in architecture, which will

likely have big impacts on outcomes and network

structure. Differences like this make "VHS versus BetaMax" analogies

inaccurate.

I'm glad that the terms "message passing" and "shared heap" seem to

have caught on when it comes to analyzing the technical differences in

approach between these systems. "Message passing" is hardly a new

term, but I think (I could be wrong) that "shared heap" is a term I

introduced here, though I didn't really state that I was doing so. I'm

glad to have seen these terms highlighted as being useful for

understanding what's going on, and I've even seen the Bluesky team use

the term "shared heap" to describe their system including around some

of the positive qualities that come from their design, and I consider

that to be a good thing.

If I were going to pull on a deeper amount of computer science

history, another way to have said things would have been "actor model"

vs "global shared tuplespaces". However, this wouldn't have been as

helpful; the important thing to deliver for me was a metaphor that

even non-CS nerds could catch onto, and sending letters was the

easiest way to do that. "Message passing" and "shared heap" thus

attached to that metaphor, and it seems like overall there has been

increased clarity for many starting with said metaphor.

Acknowledgment of scale goals

One thing I thought was good is that Bryan acknowledged Bluesky's

goals in terms of scaling and "no compromises". Let me highlight a

few places:

Other data transfer mechanisms, such as batched backfill, or routed

delivery of events (closer to "message passing") are possible and

likely to emerge. But the "huge public heap" concept is pretty

baked-in.

In particular, "big-world public spaces" with "zero compromises" is a

good highlight to me:

Given our focus on big-world public spaces, which have strong

network effects, our approach is to provide a "zero compromises"

user experience. We want Bluesky (the app) to have all the

performance, affordances, and consistency of using a centralized

platform.

And finally:

So, yes, the atproto network today involves some large

infrastructure components, including relays and AppViews, and these

might continue to grow over time. Our design goal is not to run the

entire network on small instances. It isn't peer-to-peer, and isn't

designed to run entirely on phones or Raspberry Pis. It is designed

to ensure "credible exit", adversarial interop, and other

properties, for each component of the overall system. Operating some

of these components might require collective (not individual)

resources.

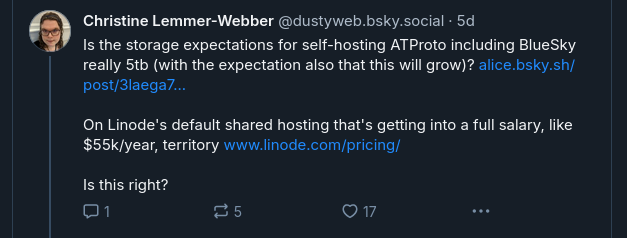

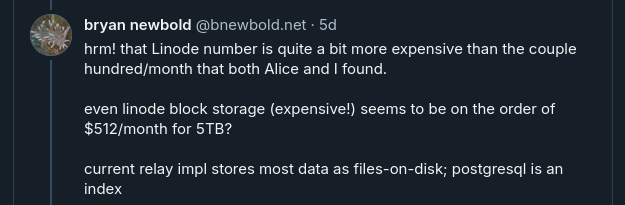

By the way, I had anticipated in my previous blogpost that we would

see the space hosting requirements for Bluesky's public network to

double within the month. I underestimated!

The cost of running a full-network, fully archiving relay has

increased over time. After recent growth, our out-of-box relay

implementation

(bigsky)

requires on the order of 16 TBytes of fast NVMe disk, and that will

grow proportional to content in the network. We have plans and paths

forward to reducing costs (including

Jetstream

and other tooling).

What's also highlighted above is that there are some new tools which

don't require the "whole network". I will comment on this at length

later.

Sizable endeavors

This section raised an eyebrow for me:

This doesn't mean only well-funded for-profit corporations can

participate! There are several examples in the fediverse of coop,

club, and non-profit services with non-trivial budgets and

infrastructure. Organizations and projects like the Internet

Archive, libera.chat, jabber.ccc.de, Signal, Let's Encrypt,

Wikipedia (including an abandoned web search project), the Debian

package archives, and others all demonstrate that non-profit orgs

have the capacity to run larger services. Many of these are running

centralized systems, but they could be participating in

decentralized networks as well.

The choice of community and nonprofit orgs here surprised me, because

for the most part I know the numbers on them. Libera.chat and and

jabber.ccc.de might be small enough, because IRC and XMPP are in

decline of use for one thing, but also because they're primarily

sending around low-volume plaintext messages which are ephemeral.

The other cases are particularly curious. The annual budgets of some

of these organizations:

These may sound like overwhelming numbers, but it is true that each

of these organizations is extremely efficient relative to the value

they're providing, especially compared to equivalent for-profit

institutions. My friend Nathan Freitas of the

Guardian Project likes to point out

that US military fighter jets cost hundreds of millions of

dollars... "when people complain about public funding of open source

infrastructure, I like to point out that funding signal is just asking

for a wing of a fighter jet!" Great point.

But for me personally, this is a strange set of choices in terms of

"non-profits/communities can host large infrastructure!" Well yes,

but not because they don't cost a lot. People often don't realize the

size and scale of running these kinds of organizations or their

infrastructure, so I'm highlighting that to show that it's not

something your local neighborhood block can just throw together out of

pocket change.

(But seriously though, could open source orgs have some of that

fighter jet wing money?)

Decentralization and federation terminology

If you are going to read any section of this writeup, if you are going

to quote any section, this one is the important one. For I believe the

terms we choose are important: how we stake the shape of language

affects what kinds of policies and actions and designs spring forth.

Language is loose, but language matters. So let us look at the

terminology we have.

A comparison of definitions

Bryan acknowledges my definitions of decentralization and federation,

and also acknowledges that perhaps Bluesky does not meet either

definition. Bryan instead "chooses his own fighter" and proposes two

different definitions of decentralization and federation from Mark

Nottingham's RFC 9518: Centralization, Decentralization, and Internet Standards.

First let us compare definitions. Usefully, Bryan highlights Mark's

definition of centralization (which I had not defined myself):

[...] "centralization" is the state of affairs where a single entity

or a small group of them can observe, capture, control, or extract

rent from the operation or use of an Internet function exclusively.

So far so good. I agree with this definition.

Now let us get onto decentralization. First my definition of

decentralization:

Decentralization is the result of a system that diffuses power

throughout its structure, so that no node holds particular power at

the center.

Now here is Bryan's definition (more accurately Mark Nottingham's

definition (more accurately, Paul Baran's definition)) of

decentralization:

[Decentralization is when] "complete reliance upon a single point is

not always required" (citing Baran, 1964)

Perhaps Bluesky matches this version of decentralization, but if so,

it is because it is an incredibly weak definition of decentralization,

at least taken independently. This may well say, taken within the

context it is provided, "users of this network may occasionally not

rely on a gatekeeper, as a treat".

Put more succinctly, the delta between the definition I gave and the

definition chosen by Bryan is:

- The discussion of power dynamics, and diffusion thereof, is removed

- The phrase complete reliance is introduced, opening acceptability

within the definition that incomplete reliance is an acceptable

part of decentralization

- The phrase not always required is introduced, opening

acceptability that even complete reliance may be acceptable, as long

as it is not always the case

When I spoke of my concerns of moving the goalpost, the delta between

the goalpost chosen in my definition and the goalpost chosen in

Bryan's chosen definition are miles away.

We'll come back to this in a second, because the choice of the

definition by Baran is more interesting when explored in its original

context.

But for now, let's examine federation. Here is my definition:

[Federation] is a technical approach to communication architecture

which achieves decentralization by many independent nodes

cooperating and communicating to be a unified whole, with no node

holding more power than the responsibility or communication of its

parts.

Here is Bryan's definition (more accurately Mark Nottingham's

definition):

[...] federation, i.e., designing a function in a way that uses

independent instances that maintain connectivity and interoperability

to provide a single cohesive service.

At first these two seem very similar. What, again is the delta?

- The discussion of power dynamics, once again, is not present.

- "Cooperation" is not present.

- And very specifically, "decentralization" and "no node holding more

power than the responsibility or communication of its parts" is not

present.

Reread the definition above and the definition I gave and compare: under

these definitions, any corporate but proprietary and internal

microservices architecture or devops platform would qualify. (Not an

original observation; thanks to Vivi for pointing

this out.) Dropping power dynamics and decentralization from the

definition reduces this to "communicating components", which isn't enough.

Bryan then goes on to acknowledge that this definition is a comparative

low bar:

What about federation? I do think that atproto involves independent

services collectively communicating to provide a cohesive and unified

whole, which both definitions touch on, and meets Mark's low-bar

definition.

However, in the context of Nottingham's paper, it's admittedly stronger,

because federation is specifically upheld as a decentralization

technique, which is missing when quoted out of context (though

Nottingham notably challenges whether or not it achieves that goal in

practice). Which turns out to be important. The "power dynamics" part

and specifically "immersing this definition in decentralization" parts

are actually really both very important parts of the definition I gave.

Bryan then goes on to acknowledge that maybe federation isn't the best

term for Bluesky, and leaves some interesting history I feel is

worthwhile including here:

Overall, I think federation isn't the best term for Bluesky to

emphasize going forward, though I also don't think it was misleading

or factually incorrect to use it to date. An early version of what

became atproto actually was peer-to-peer, with data and signing keys

on end devices (mobile phones). When that architecture was abandoned

and PDS instances were introduced, "federation" was the clearest term

to describe the new architecture. But the connotation of "federated"

with "message passing" seems to be pretty strong.

So on that note, I think it's fine to say, Bluesky is not federated, and

there's enough general acknowledgement of such. Thus it's probably best

if we move onto an examination of decentralization, and in particular,

where that definition came from.

"Decentralization" from RFC 9518, in context

Earlier I said "now here is Bryan's definition (more accurately Mark

Nottingham's definition (more accurately, Paul Baran's definition)) of

decentralization" and those nested parentheses were very intentional.

In order to understand the context in which this definition arises, we

need to understand each source.

First, let us examine Mark Nottingham's IETF independent submission,

RFC 9518: Centralization, Decentralization, and Internet Standards.

Mark Nottingham has a long and respected history of participating in

standards, and most of his work history is doing so for fairly sizable

corporate participants. From the title, one might think it a

revolutionary call-to-arms towards decentralization, but that isn't what

the RFC does at all. Instead, Nottingham's piece is best summarized by

its own words:

This document argues that, while decentralized technical standards may

be necessary to avoid centralization of Internet functions, they are

not sufficient to achieve that goal because centralization is often

caused by non-technical factors outside the control of standards

bodies. As a result, standards bodies should not fixate on preventing

all forms of centralization; instead, they should take steps to ensure

that the specifications they produce enable decentralized operation.

The emphasis is mine, but I believe captures well what the rest of the

document says. Mark examines centralization, as well as those who are

concerned about it. In the section "Centralization Can Be Harmful",

Mark's description of certain kinds of standards authors and internet

activists might as well be an accurate summation of myself:

Many engineers who participate in Internet standards efforts have an

inclination to prevent and counteract centralization because they see

the Internet's history and architecture as incompatible with it.

Mark then helpfully goes on to describe many kinds of harms that do

occur with centralization, and which "decentralization advocates" such

as myself are concerned about: power imbalance, limits on innovation,

constraints on competition, reduced availability, monoculture,

self-reinforcement.

However, the very next section is titled

"Centralization Can Be Helpful"! And Mark goes into great lengths

also about ways in which centralized systems can sometimes provide

superior service or functionality.

While Mark weighs both, the document reads as a person who authors

standards document who would like the internet to be more decentralized

where it's possible, but also operates from the "pragmatic" perspective

that things are going to re-centralize most of the time anyway, and when

they do this ultimately tends to be useful. It is also important to

realize that this is occuring in a context where many people are

worrying about increasing centralization of the internet, and wondering

to what degree standards groups should play a role. From Mark's own

words:

Centralization and decentralization are increasingly being raised in

technical standards discussions. Any claim needs to be critically

evaluated. As discussed in Section 2, not all centralization is

automatically harmful. Per Section 3, decentralization techniques do

not automatically address all centralization harms and may bring their

own risks.

Note this framing: centralization is not necessarily harmful, and

decentralization may not address problems and may cause new ones.

Rather than a rallying cry for decentralization, Mark's position is in

many ways a call for a preservation of the increasing status quo: large

corporations tend to be capturing and centralizing more of the internet,

and we should be worried about that, but should it really be the job of

standards? Remember, this is a concern within IETF and other

standards groups. Mark says:

[...] approaches like requiring a "Centralization Considerations"

section in documents, gatekeeping publication on a centralization

review, or committing significant resources to searching for

centralization in protocols are unlikely to improve the Internet.

Similarly, refusing to standardize a protocol because it does not

actively prevent all forms of centralization ignores the very limited

power that standards efforts have to do so. Almost all existing

Internet protocols -- including IP, TCP, HTTP, and DNS -- fail to

prevent centralized applications from using them. While the imprimatur

of the standards track is not without value, merely withholding it

cannot prevent centralization.

Thus, discussions should be very focused and limited, and any

proposals for decentralization should be detailed so their full

effects can be evaluated.

Mark evaluates several structural concerns, many of which I strongly

agree with. For example, Mark points out that email has, by and large,

become centralized, despite starting as a decentralized system. I fully

agree! "How does this system not result in the same re-centralization

problems which we've seen happen to email" is a question I often throw

around. And Mark also highlights paths to which standards groups may

reduce centralization.

But ultimately, the path which Mark leans most heavily into is the

section "Enable Switching":

The ability to switch between different function providers is a core

mechanism to control centralization. If users are unable to switch,

they cannot exercise choice or fully realize the value of their

efforts because, for example, "learning to use a vendor's product

takes time, and the skill may not be fully transferable to a

competitor's product if there is inadequate standardization".

Therefore, standards should have an explicit goal of facilitating

users switching between implementations and deployments of the

functions they define or enable.

Does this sound familiar? If so, it's because it's awfully close to

"credible exit"!

There is a common ring between Mark and Bryan's articles: centralization

actually provides a lot of features we want, and we don't want to lose

those, and it's going to happen anyway, so what's really important is

that users have the ability to move away. While this provides a

safety mechanism against centralization gone badly, it is not a path to

decentralization on its own. Credible exit is useful, but as a

decentralization mechanism, it isn't sufficient. If the only options in

town are Burger King and McDonalds for food, one may have a degree of

options and choice, but this really isn't satisfying to assuage my

concerns, even if Taco Bell comes into town.

What's missing from Mark's piece altogether is "Enable Participation".

Yes, email has re-centralized. But we should be upset and alarmed that

it is incredibly difficult to self-host email these days. This is a

real problem. It's not unjustified in the least to be upset about it.

And work to try to mitigate it is worthwhile.

"Decentralization" within Baran's "On Distributed Communications"

In the last subsection, we unpacked the outer parenthetical of "now here

is Bryan's definition (more accurately Mark Nottingham's definition

(more accurately, Paul Baran's definition)) of decentralization". In

this subsection, we unpack the inner parenthetical. (Can you tell that

I like lispy languages yet? Now if there was only also a hint that I

also enjoy pattern matching ...)

Citing again the definition chosen by Bryan (or more accurately ... (or

more accurately ...)):

[Decentralization is when] "complete reliance upon a single point is

not always required" (citing Baran, 1964)

Citations, in a way, are a game of telephone, and to some degree this is

inescapable for the sake of brevity in many situations. Sometimes we

must take an effort to return to the source, and here we absolutely

must.

The cited paper by Paul Baran is none other than

"On Distributed Communications: I. Introduction to Distributed Communication Networks

published by Paul Baran in 1964. There is perhaps no other paper which

has influenced networked systems as highly as this work of Baran's has.

One might assume from the outset that the paper is too dense, but I

encourage the interested reader: print it out, go read it away from your

computer, mark it up with a pen (one should know: there is no other good

way to read a paper, the internet is too full of distractions). There

is a reason the paper stands the test of time, and it is a joy to read.

Robust communication in error-prone networks! Packet switching! Wi-fi,

telephone/cable, satellite internet predicted as all mixing together in

one system! And the gall to argue that one can build it and that it

would be a dramatically superior system if we focus on having a lot of

cheap and interoperable components rather than big, heavy

centralized ones!

It may come as a surprise, then, that I have called the above definition

of decentralization too weak if I am heaping praise on Baran's paper as

such. But actually, this definition of "decentralized" is the only

time in the paper that the term comes up. How could this be?

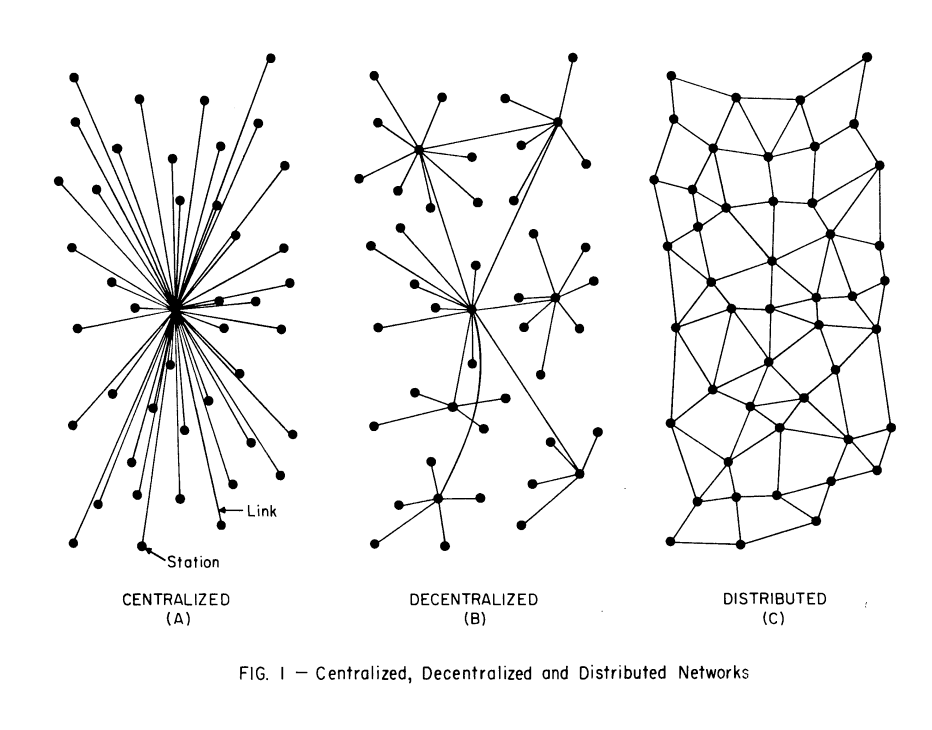

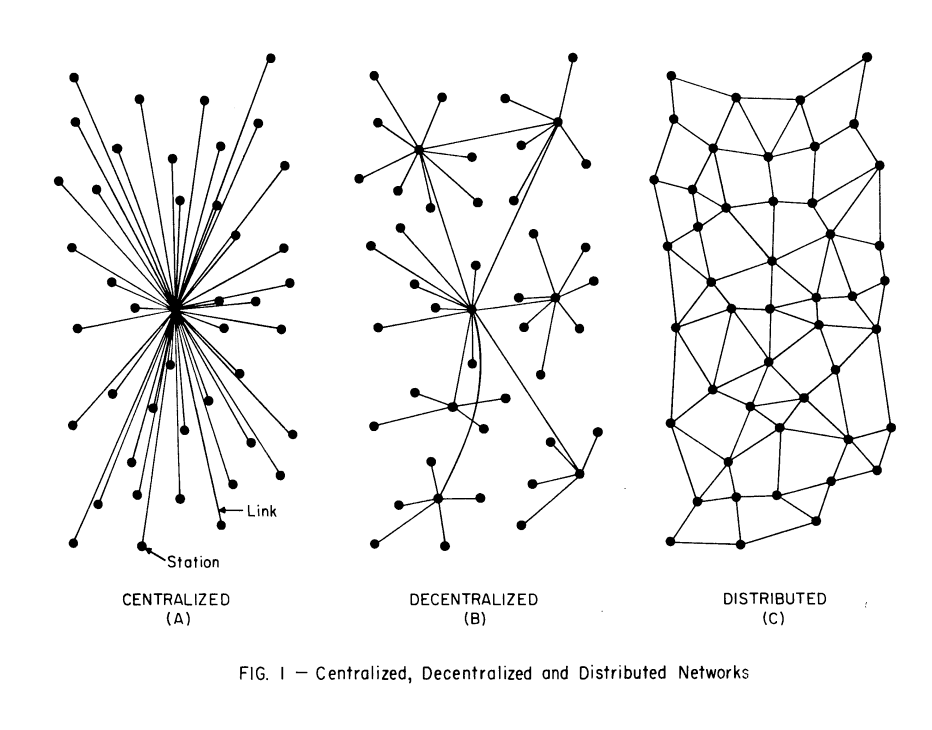

To understand, we need only look at the extremely famous "Figure 1" of

the paper which, if you have worked on "decentralized" (or

"distributed") network architecture at all, you have certainly seen:

The full paragraph linked to the cited figure is worth citing in its

entirety:

The centralized network is obviously vulnerable as destruction of a

single central node destroys communication between the end station.

In practice, a mixture of star and mesh components is used to form

communication networks. For example, type (b) in Fig. 1 shows the

hierarchical structure of a set of stars connected in the form of a

larger star with an additional link forming a loop. Such a network is

sometimes called a "decentralized" network, because complete reliance

upon a single point is not always required.

In other words, in Baran's paper, where he is defining a

new and more robust vision for what he calls "distributed networks",

he is providing "decentralized" as a pre-existing term, not his own

definition, for a topology he is criticizing for

still being centralized! (Observe! If you read the paragraph

carefully Baran is saying that "decentralized" networks like this are

still "centralized"!)

Let's observe that again. Baran is effectively saying that a tiered,

hierarchical system with many nodes, being called "decentralized"

(because that is a term that already existed for these kinds of

networks), was in fact centralized. So the very definition selected by

Mark Nottingham (and thus Bryan as well) was being criticized for being

too centralized by the original cited author!

Baran had to introduce a new term because the term "decentralized" was

already being used. However, when we talk about "centralized" vs

"decentralized" as if they are polar ends of a spectrum, we are actually

talking about type (a) of "Figure 1" being "centralized" and type (c)

being the "ideal" version of "decentralized", with (b) sometimes showing

up as kind of a grey-area space. Notably, Mark Nottingham makes no such

distinction as Baran does between "decentralized" and "distributed", yet

uses the definition of "decentralized" that instead resembles tiered,

hierarchically centralized systems... not the version of

"decentralized" to which Mark Nottingham then goes at great length to

analyze.

That is why Baran's definition of "decentralized" is so weak.

This is critical history to understand!

In other words:

- Contemporary nomenclature: "Centralized" and "Decentralized" as polar

ends of a spectrum.

- Baran nomenclature: "Centralized and "decentralized" are both

centralized topologies, but the latter is hierarchical. "Distributed"

is the more robust and revolutionary view.

Do you see it? To use the latter's definition of decentralization to

describe the former is to use a definition of centralization. This is

not a good starting point.

Baran, notably, is bold about what he calls distributed systems, and

it is important to understand Baran's vision as being bold and

revolutionary for its time. I can't resist quoting one more paragraph

before we wrap up this section (remember! nothing like the internet had

yet been proposed or envisioned as something possible before!):

It would be treacherously easy for the casual reader to dismiss the

entire concept as impractically complicated -- especially if he is

unfamiliar with the ease with which logical transformations can be

performed in a time-shared digital apparatus. The temptation to throw

up one's hands and decide that it is all "too complicated," or to say,

"It will require a mountain of equipment which we all know is

unreliable," should be deferred until the fine print has been read.

May that we all be so bold as Baran in envisioning the system we could

have!

Why is this terminology discussion so important?

Here I have, at even greater length than my previous post or even

Bryan's own response to mine, gone into great length about terminology.

But this is important. As I have stated, there are great risks in

moving the goalposts. It is hard for those who do not work on

networked systems day in and day out to make sense of any of this.

"Decentralization washing" is a real problem. I don't find it

acceptable.

Bryan "chose his fighter" with Mark Nottingham's RFC, and the choice of

fighter informs much that follows. Mark Nottingham himself is

advocating that a push too hard on decentralization is something

standards people should not be doing, and if they do, should be scoping.

Some amount of centralization, according to Mark, is useful, good, and

inevitable, and we should scope down the amount of decentralization vs

centralization topics that come up in standards groups to something

actionable. Mark's reasons are well studied, and while Mark's history

often comes from a background in representing standards on behalf of

larger corporations, I believe he would like to see decentralization

where possible, but is "pragmatic" about it.

(This is also somewhat of a personal issue for me; my participation in

standards has been generally as more "outside the system" of corporate

standards work than the average standards person, and there's a real

push and pull between how much standards orgs tend to be dominated by

corporate influence. I'm not against corporate participation, I think

it's important but... I highly recommend reading Manu Sporny's

Rebalancing How the Web is Built

which describes the governance challenges, particularly leading to

corporate capture, which tend to happen within standards orgs. One of

the only reasons I believe ActivityPub was able to be as "true to its

goals" as it was is partly that the big players refused to

participate at the time of standardization, which at the time was an

existential threat to the continuation of the group, but in retrospect

ended up being a blessing for the spec. It both is and is not an aside,

but getting further into that is a long story, and this is already a

long article.)

Mark's choice to use the definition of "decentralization" from Baran is

however dangerous to read without understanding the surrounding

context. The way Baran used the term was as a

criticism of hierarchical centralization, and was introducing a

new term as an alternative. This is why Baran's definition of

"decentralization" appears so weak: Baran was not advocating for the

ideas he was scoping under that (pre-existing in the context he was

arguing within) term.

I personally don't believe we need to support the three-word

"centralization", "decentralization", and "distributed" phrases which

Baran used, it's fine for me to have a spectrum between "centralized"

and "decentralized". But we should not conflate a situation where

"decentralization" means "tiered centralization" with the contemporary

usage of "resisting centralization".

However, all this is to say that I think Nottingham's view on

how much we should be bothering to be concerned with centralization vs

decentralization aligns well with ATProto and Bluesky's own

interpretations. "Credible exit", I still assert, is a separate view, a

particular mechanism to avoid some of the challenges of centralization

going bad, and indeed in Nottingham's own RFC, it is only one path of

several examined, but the one Nottingham appears most aligned with as

practically possible.

Regardless, I'd still say then: if Bluesky does not meet my definition

of "decentralized", the solution is not to move the goalposts. I think

I've made it clear enough, with a thorough enough reading of the

literature, of why to accept the proposed definition within Bryan's post

would be to move the goalposts. I don't think that's intentional, or

malicious, but it is the result, and I'm not satisfied with that result.

That's enough said on the topics of terminology. Let's move on.

What happens when ATProto scales down?

A specific form of scale-down which is an important design goal is

that folks building new applications (new Lexicons) can "start

small", with server needs proportional to the size of their

sub-network. We will continue to prioritize functionality that

ensures independent apps can scale down. The

"Statusphere" atproto

tutorial demonstrates this today, with a full-network AppView

fitting on tiny server instances.

I won't spend too long on this other than to say: a large portion of the

arguments for why to choose ATProto's architecture specifically was to

"not miss replies/messages", and as said in my previous article, that

requires a god's-eye view of the system. Here it's argued that ATProto

can scale down, and yes it can, but is that the architecture you

want?

Given that message passing systems, by having directed messaging, is

able to scale down quite beautifully but still interoperate

as much as one would like with a larger system, what is the value of

using an architecture which scales down with much more difficulty and

which is oblivious of external interactions without knowing all of them?

I made a claim here: ATProto doesn't scale down well. That's mainly

because to me, scaling down still means being participatory with as much

as you'd like of a wider system while still having small resources.

What I would like to analyze in greater detail is why

ATProto doesn't scale wide. To me, these two arguments are

inter-related. Let's analyze them.

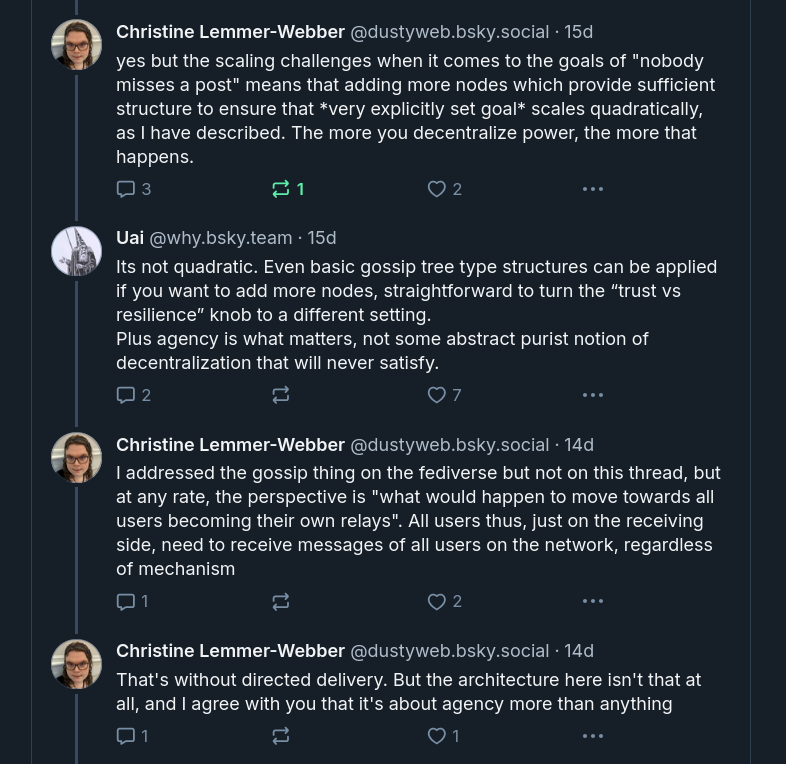

Defending my claim: decentralized ATProto has quadratic scaling costs

In my previous article, I said the following:

If this sounds infeasible to do in our metaphorical domestic

environment, that's because it is. A world of full self-hosting is

not possible with Bluesky. In fact, it is worse than the storage

requirements, because the message delivery requirements become

quadratic at the scale of full decentralization: to send a message to

one user is to send a message to all. Rather than writing one letter,

a copy of that letter must be made and delivered to every person on

earth.

However, clearly not everyone agreed with me:

"Agency" really is important to me, probably

the most important thing,

but we will leave this aside for the moment and focus on a different

phrase: "participatory infrastructure".

Was I right or wrong that as nodes are added to ATProto that the scaling

costs are quadratic? After I read this exchange, I really doubted

myself for a bit. I don't have a formal background in Computer Science;

I learned software engineering through community educational materials

and honed my knowledge through the

"school of hard thunks".

So I spent a morning on the Spritely engineering call distracting my

engineering team by walking through the problem. It's easy to get lost

in the details of thinking about the roles of the communicating

components, so Spritely's CTO, David Thompson,

decided to throw my explainer aside and work through the problem

independently. Dave came to the same conclusion I did. I also called

up one of my oldschool MIT AI Lab type buddies and asked hey, what do

you think? I think this is a quadratic scaling problem am I wrong? He

said (from vague memory of course) "I think it's pretty clear

immediately that it's quadratic. This is basic engineering

considerations, the first thing you do when you start designing a

system." Well that's a relief that I wasn't confused. But if it seemed

obvious to me, why wasn't it obvious to everyone else? "It seemed

pretty clear the way you described it to me. So why don't you just

repeat that?"

So okay, that's what I'll do.

Let's start with the following points before we begin our analysis:

- We will assume that, since ATProto has partly positioned itself as

having one of its key values be "no compromises on centralized use

cases" including "no missed messages or replies", that at minimum

ATProto cannot do worse than ActivityPub, in its current deployment,

does today. Replies and messages addressed to specific users (whether

or not addressing is on the protocol layer or extrapolated on top of

it) must, at least, be seen by the their intentional recipients.

- We will start with the assumption that the most centralized

infrastructure is one in which there is only one provider controlling

the storage and distribution of all messages: the least amount of

user participation in the operation of the network.

- We will, on the flip side, consider decentralization to be the

inverse, with the most amount of user participation in the operation

of the network. In other words, "every user fully self hosts".

- We will also take the lessons of my previous post at face value; just

as blogging is decentralized but Google (and Google Reader) are not,

it is not enough to have just PDS'es in Bluesky be self-hosted. When

we say self-hosted, we really mean self-hosted: users are

participating in the distribution of their content.

- We will consider this a gradient. We can analyze the system from the

greatest extreme of centralization which can "scale towards" the

greatest degree of decentralization.

- We will analyze both in terms of the load of a single participant on

the network but also in terms of the amount of network traffic as a

whole.

With that in place, it's time to analyze the "message passing"

architecture vs the "shared heap" architecture in terms of how they

perform when scaling.

Here is my assertion in terms of the network costs of scaling towards

decentralization, before I back it up (I will give the computer

science'y terms then explain in plain language after):

- There is an inherent linear cost to users participating on the

network, insofar as for

n users, there will always be an O(n)

cost of operation. "Message passing" systems such as ActivityPub, at full

decentralization:

- Operate at

O(1) from a single user's perspective - Operate at

O(n) from a whole-network perspective (and this is, by

definition, the best you can do)

"Public no-missed-messages shared-heap" systems such as ATProto, at

full decentralization:

In other words, as we make our systems more decentralized, message

passing systems handle things fairly fine. Individual nodes can

participate on the network no matter how big the network gets. Zooming

out, as more users are added to the decentralized network, the message

load is roughly the normal amount of adding more users to the network.

However, as we make things more decentralized for the public shared

heap model, everything explodes, both on the individual node level, but

especially when we zoom out to how many messages need to be sent.

And there is no solution to this without adding directed message

passing. Another way to say this is: to fix a system like ATProto to

allow for self-hosting, you have to ultimately fundamentally change it

to be a lot more like a system like ActivityPub.

This can easy to get lost about; the example above of stating that

"gossip" can improve things indicates that talking about message

sending is confusing the matter. It will be easier to understand by

thinking about message receiving.

To start with a very small example by which we can clearly observe the

explosion, let's set up a highly simplified scenario. First let me give

the parameters, then I will tell a story. (You can skip the following

paragraph to jump to the story if that's more your thing.)

That n number we mentioned previously will now stand for the

number-of-users on the network. We will also introduce m which will

be number-of-machines, which represents the number nodes on the

network. Decentralizing the system involves n moving towards m, so

at full decentralization, n and m would be the same; at intermediate

levels of decentralization it may be less, but n converges towards

m as we decentralize. Each user is individually somewhat chatty, and

sends a number of daily-messages-per-user, but we can average these

out across all users, so this is just a constant which for our cases we

can simplify to 1 for a modeled scenario (though it can scale up and

down, it does not affect the rate of growth). Likewise, each message

individually sent by a user has a

number-of-intended-recipients-per-message, which we can average by the

amount of people who were individually intended to receive such message,

such as directed messages or subscribers in a publish-subscribe system;

however this too can be averaged, so we can also simplify this to 1

(so this also does not affect the rate of growth).

Lost? No worries. Let's tell a story.

In the beginning of our network, we have 26 users, which conveniently

for us map to each letter of the English alphabet: [Alice, Bob, Carol, ... Zack]. Each user sends one message per day, which is intended to

have one recipient. (This may sound unrealistic, but this is fine to

do to model our scenario.) To simplify things, we'll have each user

send a message in a ring: Alice sends a message to Bob, Bob sends

a message to Carol, and so on, all the way up to Zack, who simply we

wrap around and have message Alice. This could be because these

messages have specific intended recipients or it could be because Bob

is the sole "follower" of Alice's posts, Carol is the sole

"follower" of Bob's, etc.

Let's look at what happens in a single day under both systems.

Under message passing, Alice sends her message to Bob. Only Bob

need receive the message. So on and so forth.

- From an individual self-hosted server, only one message is

passed per day: 1.

- From the fully decentralized network, the total number of messages

passed, zooming out, is the number of participants in the network: 26.

Under the public-gods-eye-view-shared-heap model, each user must know

of all messages to know what may be relevant. Each user must

receive all messages.

From an individual self-hosted server, 26 messages must be received.

Zooming out, the number of messages which must be transmitted in the

day is 26 * 26: 676, since each user receives each message.

Okay, so what does that mean? How bad is this? With 26 users, this

doesn't sound like so much. Now let's add 5 users.

But we aren't actually running networks of 26 users. We are running

networks of millions of users. What would happen if we had a million

self-hosted users and five new users were added to the network? Zooming

out, once again, the message passing system simply has five new messages

sent. Under the public shared heap model, it is 10,000,025 new messages

sent! For adding five new self-hosted users! (And that's even just

with our simplified model of only sending one message per day per

user!)

Maybe this sounds silly, if you're a Bluesky enthusiast. I could hear

you saying: well Christine, we really aren't planning on everyone self

hosting. Yes, but how many nodes can participate in the system at all?

The fediverse currently hosts around 27,000 servers (many more users,

but let's focus on servers). Adding just 5 more servers would be a blip

in terms of the affect on the network. Adding 5 more servers to an

ATProto ecosystem with that many fully participating nodes would be an

exhausting number of additional messages sent on the network. ATProto

does not scale wide: it's a liability to add more fully participating

nodes onto the network. Meaningfully self-hosting ATProto is a risk

to the ATProto network, there is active reason to disincentivize it for

those already participating. But it's not just that. Spreading things

around so that more full Bluesky-like nodes are present is something

server operators will have to come to discourage if they don't want

their already existing high hosting costs to not skyrocket.

Now, what about that mention of "well gossip could help"? This is why I

said it is important to think of messages as they are received as

opposed to how they are sent. The scenario I gave above was

a more ideal scenario than gossip. In a gossip protocol, a node often

receives messages more than once. The scenario I gave was more

generous: messages are only received once. You can't know information

unless it's told to you (well, unless you can infer it, but that's not

relevant for this case). It's best to think about receiving.

Architecture matters. There is a reason message passing exists. I

don't believe in the distinction between "it's a technical problem" or

"it's a social problem" most of the time when designing systems, because

it's usually both: the kinds of social power dynamics we can have are

informed by the power dynamics of our tech and vice versa. Who can

participate here? I agree with the agency concern, I am always deeply

concerned with agency, but here agency depends on providers. How big

do they have to be? How many of them can there be?

A lot of hope in Bluesky and ATProto is in terms of the dreams of what

seems possible. Well, for decentralization of Bluesky and ATProto to

even be possible, it must change its architecture fundamentally.

ATProto doesn't need to switch to ActivityPub, but in order to become a

real decentralized protocol, it has to become a lot more like it.

Reframing portable identity

Bryan has some nice responses to the did:plc stuff in his article, I

won't go over it again in depth here. I'll just say it was nice to see.

I actually think that despite all the concerns I laid out about the

centralization of did:plc, it's not something I'm all too worried

about in terms of the governance of the ledger of updates. It seems

like the right things are being done so that did:plc can be audited by

multiple parties in terms of working towards a certificate transparency

log, etc. That's good to hear.

My bigger concern is that if Bluesky shuts down tomorrow or is bought by

a larger player, in practice if Bluesky refuses to allow for a path to

rotating keys to move away, it'll be hard to do anything about that.

Still, Bluesky is doing more work in the decentralized identity space

than most at this point. I want to give them some credit there, and end

this little subsection on that positive note.

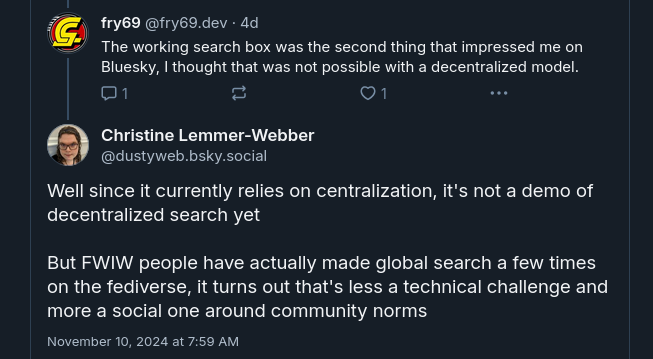

Bluesky's expectations of public content vs community expectations

ATProto's main design is built upon replicating and indexing the

firehose. That is its fundamental design choice and method of

operation.

I won't go into this too far here other than to say, I'm not sure this

is in alignment with what many of its users want. And we're seeing

this, increasingly, as users are being upset about finding out that

other providers have replicated and indexed their data. This is

happening in a variety of ways, from LLM training concerns, to

moderation concerns, etc.

I won't say too much more on that. I think it's just... this all just

gives me the feeling that the "speech vs reach" approach, and the idea

of a global public firehose, a "global town square" type approach... it

all feels very web 2.0, very "Millennial social media"... for Millenials,

by Millenials, trying to capture the idea that society would be better

if we all got everyone to talk to each other at once.

I think Bluesky is doing about as good a job as a group of people can

do with the design they have and are trying to preserve. But I don't

think the global context-collapse firehose works, and I'm not sure it's

what users want it either, and if they do, they really seem to want both

strong central control to meet their needs but also to not have strong

central control be a thing that exists when it doesn't.

And who can blame users for that? An alternative can not usually be

envisioned unless an alternative is presented.

So, what's the alternative?

On the values and design goals of projects and protocols

One thing I appreciated was where Bryan laid out Bluesky's values and

design goals:

Over the summer, I wrote a summary of Bluesky's progress on atproto on

my personal blog:

"Progress on atproto Values and Value Proposition".

Christine identified "Credible Exit" as one of these key

properties. Some of the other high-level goals mentioned there were:

- Own Your Identity and Data

- Algorithmic Choice

- Composable Multi-Party Moderation

- Foundation for New Apps

Any of these could be analyzed individually; I have my own

self-assessment of our progress in the linked article.

I think this is great for Bryan to lay out. They're a nice set of

goals. (I don't love the term "own your data" for various "intellectual

property" term-confusion adjacent reasons, but that's an aside; the

intended meaning is good.) Overall I think this is a pretty

reasonably set of goals and you can see why they would inform the design

of Bluesky significantly. You don't see many projects lay out their

values like this, and it would be good to see done more often.

On that note...

One thing I'd be curious to see is an equivalent set of design goals

for ActivityPub (or for Spritely's work,

for that matter). This might exist somewhere obvious and I just

haven't seen it. It might all differ for the distinct original

projects and individuals which participated in the standards process.

This was a nice ask to make. Let me address them separately.

ActivityPub's values and design goals

In a way, it's a bit harder for me to talk about the values and design

goals of ActivityPub. It happened in a larger standards group and

involved a lot of passing of hands. I think if I were to be robust

about it, I would also ask Evan Prodromou, Erin Shepherd, and Amy Guy to

weigh in, and maybe they should; I think it would be nice to hear. But

since I work with Jessica Tallon (and I'm kind of tired of writing this

and want to just get it out there) we had a brief talk this morning and

I'll just discuss what we talked about.

The SocialWG charter

is informative, first of all. It says the following:

The Social Web Working Group will create Recommendation Track

deliverables that standardize a common JSON-based syntax for social

data, a client-side API, and a Web protocol for federating social

information such as status updates. This should allow Web application

developers to embed and facilitate access to social communication on

the Web. The client-side API produced by this Working Group should be

capable of being deployed in a mobile environment and based on HTML5

and the Open Web Platform. For definitions of terms such as "social"

and "activity", please see the W3C Social XG report A Standards-based,

Open and Privacy-aware Social Web.

There are a number of use cases that the work of this Working Group

will enable, including but not limited to:

- User control of personal data: Some users would like to have

autonomous control over their own social data, and share their data

selectively across various systems. For an example (based on the

IndieWeb initiative), a user could host their own blog and use

federated status updates to both push and pull their social

information across a number of different social networking sites.

- Cross-Organization Ad-hoc Federation: If two organizations wish

to co-operate jointly on a venture, they currently face the problem

of securely interoperating two vastly different systems with

different kinds of access control and messaging systems. An

interoperable system that is based on the federation of

decentralized status updates and private groups can help two

organizations communicate in a decentralized manner.

- Embedded Experiences: When a user is involved in a social

process, often a particular action in a status update may need to

cause the triggering of an application. For example, a travel

request may need to redirect a user to the company's travel

agent. Rather than re-direct the user, this interaction could be

securely embedded within page itself.

- Enterprise Social Business: In any enterprise, different

systems need to communicate with each other about the status of

various well-defined business processes without having crucial

information lost in e-mail. A system built on the federation of

decentralized status updates with semantics can help replace email

within an enterprise for crucial business processes.

I think the "user control of personal data" is kind of like "owning your

own data" but with terminology I am more comfortable with personally.

Cooperation, even if organization-focused, is there, and embedding is I

guess also present. The "enterprise" use case... well, I can't say that

ever ended up being important to me, but "business-to-business" use

cases is partly how the Social Web Working Group was able to describe

that it would have enough W3C member organization support to be able to

run as a group (which the corporate members quickly dropped out, leaving

a pile of independent spec authors... in most ways for the best for the

specs, but it seemed like an existential crisis at the time).

But those don't really speak as values to me. When Jessica and I spoke,

we identified, from our memories (and without looking at the above):

- The need to provide a federation API and client-to-server api for

federated social networks

- Relatively easy to implement

- Feasible to self-host without relying on big players

- Social network domain agnosticism: entirely different kinds of

applications should be able to usefully talk to and collaborate with

each other with the same protocol

- Flexibility and extensibility (which fell out of json-ld for

ActivityPub, though it could have been accomplished other ways)

- A unified design for client-to-server and server-to-server. This was

important for ActivityPub at least. Amy Guy ultimately did the

important work of separating the two enough where you could just

implement one or the other.

- An implementation guide which told a story, included in the spec.

(Well, maybe I was the only one who really was opinionated about

that, but I still do think it was one of the things that lead AP to

be successful.)

In some ways though, that still doesn't speak enough of values to me,

though. I added this late in the spec, and I kind of did it without

consulting anyone until after the fact, sneaking it into a commit where

I was adding acknowledgments. It felt important, and ultimately it

turned out that everyone else in the group liked it a lot. Here it is,

the final line of the ActivityPub spec:

This document is dedicated to all citizens of planet Earth.

You deserve freedom of communication; we hope we have contributed in

some part, however small, towards that goal and right.

Spritely's values and design goals

Spritely is the decentralized networking

research organization I'm the head of. We're trying to build the next

generation of internet infrastructure, and I think we're doing

incredibly cool things.

It's easier for me to talk about the values of Spritely than

ActivityPub, having founded the project technically from the beginning

and co-founded it organizationally. Here is the original mission

statement which Karen Sandler and I put together:

The purpose of The Spritely Institute is to advance networked user

freedom. People deserve the right to communicate and have communication

systems which respect their agency and autonomy. Communities deserve

the right to organize, govern, and protect and enrich their members.

All of these are natural outgrowths of applying the principles of

fundamental human rights to networked systems.

Achieving these goals requires dedicated effort. The Spritely

Foundation stewards the standardization and base implementation for

decentralized networked communities, promotes user freedom and agency of

participants on the network, develops the relevant technologies as free,

libre, and open source software, and facilitates the framing and

narrative of network freedom.

But still, though we have a mission statement, we haven't written out a

bullet point list like this before and so I tried to gather Spritely

staff input on this:

- Secure collaboration: Spritely is trying to enable safe

cooperation between individuals and communities in an unsafe world.

We are working on tools to make this possible.

- Networks of consent: The cooperation mechanism we use is

capability security, which allows for consent-granted mechanisms

which are intentional, granted, contextual, accountable, and

revocable. Rather than positioning trust as all-or-nothing or

advocating for "zero trust" environments, we consider trust as

something fundamental to cooperation, but it's also something that is

built. We want individuals and communities to be able to build

trust to collaborate cooperatively together.

- Healthy communities: We must build tech that allows communities

to self-govern according to their needs, which vary widely from

community to community. We may not know all of these needs or

mechanisms required for all communities in advance, but we should

have the building blocks so communities can easily put them in place.

- User empowerment and fostering agency: We believe in users having

the freedom to communicate, but also to be able to live healthy lives

protected from dangerous or bad interactions. We want users to be

able to live the lives they want to live, as agents in the system, to

the degree that it does not harm the agency of other users in the

system. Maximizing agency and minimizing subjection, not just for

you and me, but for everyone, is thus is a foundation.

- Contextual communication: There is no "global town square", and

we are deeply concerned about

context collapse.

Communication and collaboration should happen from contextual flows.

- Decentralized is the default: We are building technology

foundations on top of which then the rest of our user-facing

technology is built. These foundations change the game: instead of

peer-to-peer, decentralized, secure tech being the realm of experts,

it's the default output of software built on top of our tech.

- Participatory, gatekeeper-free technology: Everyone should be

able to participate in the tech, without gatekeepers. This means we

have a high bar for our tech being possible for individuals to

meaningfully run and for a wide variety of participants to be able to

cooperate on the network at once.

- We should not pretend we can prevent what we cannot: Much harm

is caused by giving people the impression that we provide features

and guarantees that we cannot provide. We should be clear about the

limitations of our architecture, because if we don't, users may

believe they are operating with safety mechanisms which they do not

have, and may thus be hurt in ways they do not expect.

- Contribute to the commons: We are a research institution, and

everything we build is free and open source software, user-freedom

empowering tech and documentation. This also informs our choice to

run the Spritely Institute, organizationally, as a nonprofit building

technology for the public good.

- Fun is a revolutionary act: The reason technology tends to

succeed is that people enjoy using it and get excited about it.

We care deeply about human rights and activism. This is not in

opposition to building tech and a community environment that fosters

a sense of fun; planned carefully, fun is at the core of getting

people to understand and adopt any technology we make.

I will note that the second to last post, contributing to the commons,

makes running the Spritely Institute challenging in so far as the

commons, famously, benefits everyone but is difficult to fund. If the

above speaks to you, I will note that the Spritely Institute is, at the

time of writing,

running a supporter drive,

and we could really use your support. Thanks. 💜

This is not a post about Spritely, but I appreciate that Bryan invited

me talking about Spritely a bit here. And ultimately, this is

important, because I would next like to talk about the present and the

future, and the world that I think we can build.

Where to from here?

I am relieved that the previous piece was overall received well and was

not perceived as me "attacking" Bluesky. I hope that this piece can be

seen the same way. I may have been "harshly analytical" in my analysis

at times, but I have tried to not be mean. I care about the topics

discussed within this blogpost, and that's why I spent so much time on

them. I know Bryan feels the same way, and one thing we both agree on

is that we don't want to be caught in an eternal back-and-forth: we want

to build the future.

But building the future does mean clear communication about terminology.

I will (quasi)quote Jonathan Rees again, as I have previously when

talking about the nature of language

and defining terminology:

Language is a continuous reverse engineering effort between all

parties involved.

(Somewhat humorously, I seem to adjust the phrasing of this

quoting-from-memory just slightly every time I quote it.)

If we aren't careful and active in trying to understand each other,

words can easily lose their meaning. They can even lose their meaning

when shifting between defined contexts over time. The fact that Baran

defined the term "decentralization" as a particular kind of

centralization was because he was responding to a context in which that

term had already been defined (and thus introducing a new term

"distributed" to describe what we might call "decentralization"). The

fact that today we use "centralization" and "decentralization" as two

ends of a spectrum is also fine. I don't think Bryan quoting Mark

quoting Baran in this way and thus introducing this error was

intentional, but ultimately it helps explain exactly why the term

chosen produced a real risk of decentralization-washing.

I agree that Bluesky does use some decentralization techniques in

interesting and useful ways. These enable "credible exit", and are also

key to enabling some of the other values and design goals which Bryan

articulated Bluesky and ATProto as having. But to me, a system which

does not permit user participation in its infrastructure and which is

dependent on a few centralized gatekeepers is not itself decentralized.

So what of my analysis of the public-global-gods-eye-view-shared-heap

approach as growing quadratically in complexity as the system

decentralizes? I'm not trying to be rude in any way. I made a

statement about the behavior of the system algorithmically, and it felt

important that I not only assess whether or not that statement was true

because if it wasn't true then I would want to understand myself and

retract it. But there's interest and belief right now by many people

that ATProto can be "self hosted". It's important, at least, to

understand to the degree which that simply, under the current

architecture, it is not possible to do. Especially because right now a

lot of people are operating on this information out of belief in and

hope for the future. If my assertion about the quadratic explosion

problems of meaningfully decentralizing ATProto are false, and that it

is possible for self-hosting to become common in the system with the

properties that Bluesky has set out as being key features still being

possible to be preserved, then I will welcome and retract that

assertion.

However, I suspect that the reality is that I am not wrong, and instead

what we will see is a shift in expectations about what is possible for

Bluesky to be decentralized and in what capacity. Some people will be

upset to have a new realization about what is and isn't possible, some

people will simply update their expectations and say that having only a

few large players be able to provide a Bluesky-like experience is

actually good enough for them (and that what they're interested in

instead is API-consumer-and-redistributor features on top of Bluesky's

API), and the majority of the network will have the same level concern

they have always had: none.

The reality is that most of Bluesky's userbase doesn't know or care

about or understand the degree to which Bluesky is decentralized, except

for potentially as a reassurance that "the same thing can't happen here"

as happened on X-Twitter. "Decentralization" is not the escape hatch

people think it might be in Bluesky, but it's true that "credible exit"

may be. However, the credibility of that exit currently predicates on

another organization of the same cost and complexity of Bluesky standing

in if-or-when Bluesky ends up becoming unsatisfying to its users.

But the indifference towards Bluesky's "credible exit", indeed the

indifference towards very architecture on which Bluesky is built,

puts Bluesky at an immediate collision course of expectations.

ATProto's entire design is built on the foundational expectation of

replicating and indexing its content by anyone, but the discovery that

this is possible for purposes which users are not excited about has

begun to lead to an increased backlash by users, many of whom are

increasingly asking for solutions which are effectively centralized.

To me, this collision course is unsurprising, and I am empathetic

towards users insofar as that I think we are seeing that the global

public firehose worldview is perhaps not the right way to do things. I

laid out a different set of values that Spritely is pursuing, and I

think that a system that encompasses these values is a system which

better fits the needs of users. I think we need systems which empower

users and healthy communities, secure collaboration, and all the other

values we put out above. Those are the design goals, but Spritely is on

a longer roadmap in terms of deliverables than Bluesky is. And Bluesky

has a userbase now. So perhaps this observation sounds thoroughly

unhelpful. I don't know. But I will say I am not surprised to see that

the vibes on Bluesky shifted dramatically between three weeks ago when I

wrote the first article and today. In many ways, Bluesky is

speedrunning the history of Twitter. Investor pressure towards

centralization compounded with users who are upset to find their content

replicated and indexed by people they don't like will likely combine

into a strong push to restrict Bluesky's API, and I'm not sure myself

how this will play out for certain.

And all of that sounds fairly negative, so let me shift towards

something positive.

I still do truly believe that "credible exit" is a worthy goal.

Actually, I think that (perhaps with one mentioned wording change) all

of Bluesky's stated goals are actually quite good. I think Bluesky

should continue to pursue them. And I think Bluesky has a team that is

interested in doing so. There may be opportunities to share knowledge

and collaborate on solutions between Bluesky and other projects,

including those I work on. I know Bryan and I are both interested in

such. And I said in the previous article how much I respect Jay Graber,

and that's true. I also respect Bryan Newbold tremendously. One thing

is true for certain: Bryan is a believer in all of the ideals he

previously stated. I respect him for that. I would like to see those

ideals succeed as far as they possibly can. Perhaps there are even ways

to do so together. I will not waver in my goals and values, but I

am a strong believer in collaboration where it is fruitful.

And that is the conclusion to what I have to say on the matters of

Bluesky and decentralization. I will probably comment on the fediverse

and Bluesky itself, but I don't think I will write another blogpost like

these two mega-posts I have written. I am not personally interested in

going back-and-forth on this any longer. More than I am interested in

laying out concerns, by far, I am interested in building the future.

Thanks for listening.